God is With Us in the Desert

Reflection on the Readings for the Second Sunday in Lent, Year C.

In this reflection, I touch on the presence of God with us, the desire for heaven that is stoked by prayer, and the purification necessary to continue on our journey of union with God.

The Transfiguration is God’s promise that, not only will he lead us into the promised land, but he will accompany us with his presence along the way.

The psalmist’s prayer, “Your presence, O LORD, I seek. Hide not your face from me,” is the prayer of Moses and Elijah, both of whom encountered God on Mt. Sinai but were unable to see his face. Now, at the transfiguration, they are finally able to look on the face of God and converse with him in the person of Jesus Christ, in whom “dwells the whole fullness of the deity bodily” (Colossians 2:9).

Luke tells us that Moses and Elijah spoke with Jesus about “his exodus.” Shortly after they came down from the mountain, Jesus “set his face toward Jerusalem” Luke 9:51). He began his exodus toward the New Jerusalem of heaven, which went by way of the cross. In the transfiguration we have another reminder of the original Exodus: the glory-cloud, or shekinah, descends on Jesus and envelopes those around him. This is the cloud that descended on the meeting tent in the desert, and later on the temple in Jerusalem, as a visible sign of the awesome and mysterious presence of God. Though this presence remained awesome and unfathomable, it was also a sign of God’s merciful care for his people. That he, the All Holy One, would live and travel with his people as they passed through the pain and trials of the desert, showed that he is a merciful God who is concerned for his people’s well-being. Even when they sin and complain and lose trust in God, he still desires to dwell with them and lead them to the promised land.

As the Jewish people celebrated the Feast of Tabernacles through the centuries, calling to mind God’s desire to dwell in a tent with them in the desert, they looked forward to the permanent presence of God which would bring stability and safety to their lives. This longing of God’s people was perhaps purest in people like Moses and Elijah, who strove to follow the law and be faithful, and who came so close to God’s glory, yet were never granted a vision of his face. This desire was granted when the “Word was made flesh, and made his tabernacle among us” (John 1:14).

This desire also finds voice in the second reading, from St. Paul’s letter to the Philippians: “Our citizenship is in heaven.” A true disciple knows his homeland is far off, and he is on a journey of exodus to that place. That journey must go by way of the cross, since we are living according to the pattern of Jesus’ life. There are those who choose not to take this exodus, who cling to the “flesh pots of Egypt”(Exodus 16:3) – the pleasures of life. These, says St. Paul, are “enemies of the cross of Christ…Their end is destruction.Their God is their stomach; their glory is in their shame.”

During Lent we are especially reminded that we are on an arduous journey toward the promised land – the place of stability, divine presence, and perfect relationship with God. We are reminded of the difficult reality of the cross, the sine qua non of our journey toward heaven, which is a purification from all that would separate us from God. When the romanticism of our Lenten promises fades, and when are presented with the pleasures of life, it is easy to turn back towards the slavery of sin and see it as freedom. We may even, like the Israelites, fall into infidelity and idol worship.

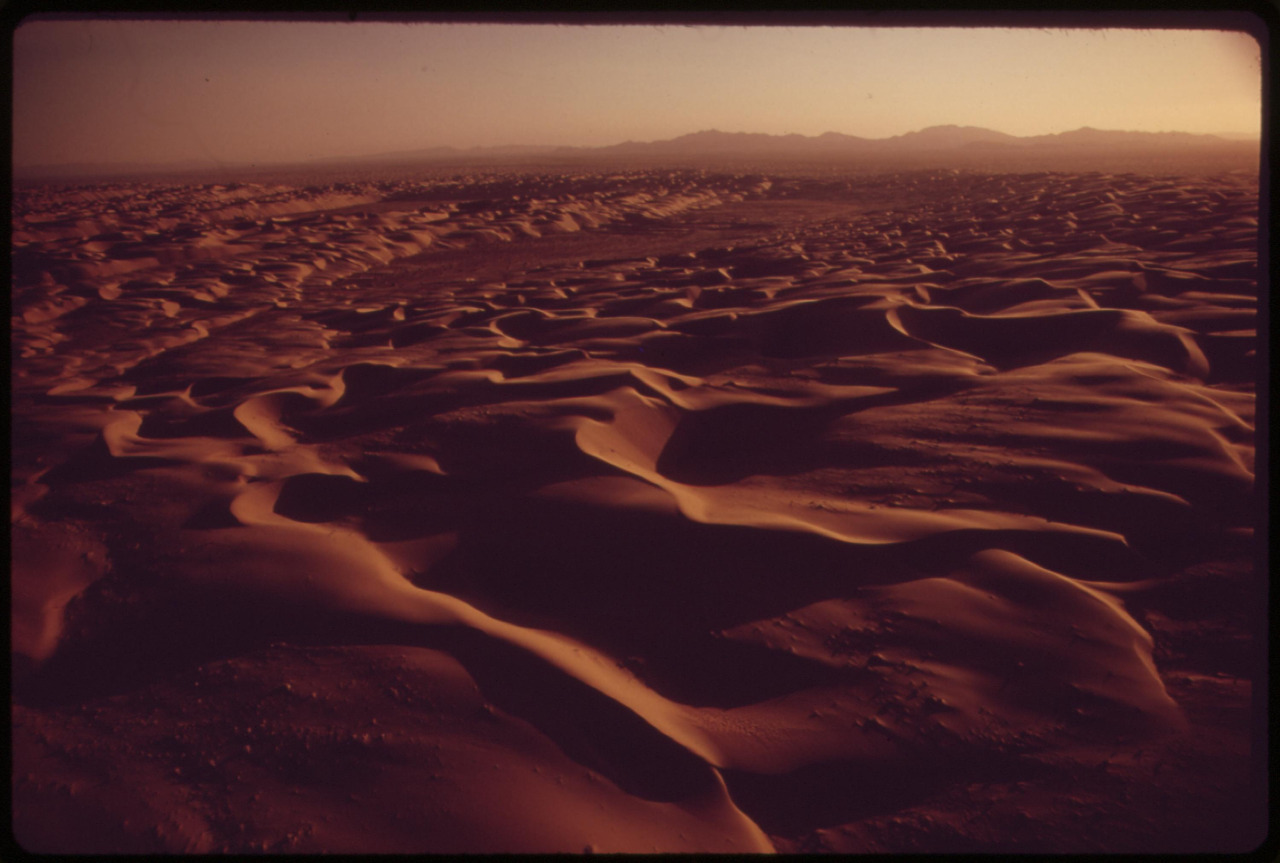

The promised land can seem very far off for us. The stable, intimate relationship with God that many of the saints began to enjoy even in this life seems like a thing of legend, or at least something for a different class of people. We can begin to fall into the all-too-common Christian error that says, “God will meet me when I become a better version of myself, when I obtain this or that virtue, or when I no longer have this obstacle to my spiritual life.” But the transfiguration shows us the opposite is true. God is with us in our difficulties. He cares about the trials we are passing through. If we feel we don’t have time for prayer, he is there to stoke the desire to see his face. If we think that we are unworthy to come into his presence, he is there to overshadow us and draw us to him anyway. If our prayer is dry and difficult, he is there to suffer with us and walk with us through the desert. We need only learn to practice the presence of God.

The transfiguration dispels the myth of self-perfection by teaching us that it is Jesus’ initiative, not our own, that draws us into union with him. We must cooperate, but even this is enabled by grace. Scripture is the greatest aid to this encounter. Like Peter, James, and John, we can have a encounter with the people in scripture through daily meditation such as Lectio Divina, Ignatian Prayer, or the rosary. This is essential to enkindle the fervor to courageously pass through the spiritual desert of this life in a living quest for the face of God.

We should also notice the times when we don’t desire to see God’s face. Spiritual lethargy results from attachments to earthly things and a lack of trust in the God who wants to make us holy. Jesus wants to purify us of these attachments and lack of trust. We can also examine our lives, noticing those things which, though in and of themselves aren’t sinful, can dull the interior senses: cell phones, TV, movies, aimlessly browsing the internet. Besides putting me in the occasion for sin, these constant stimuli dull my spiritual desires. To truly grow in union with Jesus, active purification – which begins with our individual initiative – is necessary.

The brightness of Jesus’ garments and the dark clouds remind us that there is also a passive purificationm whose initiative is God’s, that is necessary. While much is revealed in our encounter with God, there will always be infinitely more that is concealed. When a person who has put continual effort into prayer and active purification is brought by Christ to a place where his or her own faculties can’t reach, the Holy Spirit himself begins to purify the soul. This is a time of darkness, because the human light of reason cannot penetrate God’s mystery. It is a place of detachment, even from spiritual consolation or former ways of praying. Peter is attached to the glorious appearance of Moses and Elijah, and wants to cling to this experience. As good as it is, it is not God. So the presence of God overshadows him, stunning him, in order to purify him and focus him on Jesus alone.

If we are serious about taking up our cross and following Christ, and if we want to allow each moment of this life to be a step through the desert toward our homeland of heaven, then authentic Christian prayer is essential. The transfiguration reminds us of the elements of this prayer: unworthy though we are, we can pray with Scripture every day. This prayer is initiated and sustained by Christ’s initiative; it requires our cooperation and continual active purification. And we should always be ready for the Holy Spirit to purify us even of attachments to good things.

Above all, The Lord wants us to remember that he is there for us, overshadowing us with his presence. He accompanies us in the spiritual desert of this life even when we have fallen into sin. We need only turn back to him and say,

Hear, O LORD, the sound of my call;

have pity on me, and answer me.

Of you my heart speaks; you my glance seeks.

Your presence, O LORD, I seek.

Hide not your face from me.

___

Image Credit: To Beseech Thee, Angelo Juan Ramos. License.