Mercy Cures Our Numbness

Reflections on the readings for the Eleventh Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year C.

David was numb to sins. He was numb to God, and to the dignity of Bathsheba and her husband Uriah, the Hittite. David began with a small sin, that of sloth or laziness: “At the turn of the year, the time when kings go to war, David sent out Joab along with his officers and all Israel, and they laid waste the Ammonites and besieged Rabbah. David himself remained in Jerusalem.” He neglected his duty and stayed back from the battle. In his lazy boredom, he went wandering on a rooftop and spied Bathsheba bathing. Laziness turns to lust. Then to all-out adultery. And then, when Bathsheba was found to be pregnant, David had her husband killed. Murder.

We become numb to God and to others’ dignity beginning with small venial sins. Lust, adultery, and murder are possible when we have lost all feeling for the unique dignity of others. It’s like the story of the Inuits whose village was plagued by a wolf. They took a knife and dipped it in seal’s blood. The froze the blood, then dipped the knife back in. They did this several times, then put the knife outside on a stick. At night the wolf came, drawn by the smell of blood. He licked the bloodsickle, and continued licking until his tongue became numb. As he licked further, the blade sliced his tongue and he licked his own blood. But he couldn’t feel it, because he had grown numb. As he went away, he was weakened and left a trail of blood that allowed the Inuits to easily track and kill him.

This is what happened to David, and what led him to deadly sin. It is also what happened to Simon, the pharisee, in today’s Gospel. The sin of pride made him insensitive not just to Jesus’ divinity, but to his humanity. Unlike the sinful woman, he failed to offer even the basic social niceties that were expected of a host in first century Middle Eastern culture:

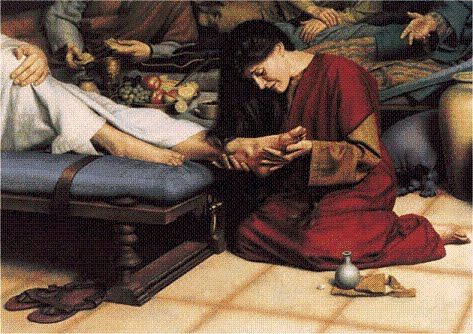

When I entered your house, you did not give me water for my feet, but she has bathed them with her tears and wiped them with her hair. You did not give me a kiss, but she has not ceased kissing my feet since the time I entered. You did not anoint my head with oil, but she anointed my feet with ointment.

When we are numb to human dignity, we are also numb to God’s presence: “If this man were a prophet, he would know who and what sort of woman this is who is touching him, that she is a sinner.” Of course Jesus knew that she was a sinner, and Jesus even knew the pharisee’s own thoughts. But the pharisee, in his numbness to God and humanity, had created his own narrow categories that didn’t allow for the possibility of mercy, or of physical contact between God and sinful humanity.

But the woman knows the cure for this numbness: repentance and mercy. We who are wounded by sin are afraid to draw near to God or to others in an authentic way, because their presence makes the sting of our wounds return. But that sting is salved by the ointment of Jesus’ mercy. This allows us to live a new life, freed from the confining boundaries that we’ve created to protect ourselves from authentic personal contact:

I have been crucified with Christ; yet I live, no longer I, but Christ lives in me; insofar as I now live in the flesh, I live by faith in the Son of God who has loved me and given himself up for me.

To die to our pride and acknowledge that there is no way to make up for our sins is an act of faith in Christ. We are no longer confined by our weaknesses and past choices. Living out of this faith, we are free to love God and other humans, like the woman who kissed Jesus’ feet. When I know that God forgives me not just of 500 days’ wages of debt, but of an eternity of punishment, I no longer have to prop myself up. I am free.

And the weaknesses and sinfulness of other people, as painful and difficult as it is, becomes a reminder of my own weakness and Jesus’ mercy. It becomes an impetus to continue growing in perfect love. When others irritate me and rub my wounds, it’s a reminder to seek further healing and mercy from Jesus – for myself first, and then for others.

Last weekend I was blessed to spend a lot of time with Dan Burke, the director of the National Catholic Register and founder of the Avila Institute and SpiritualDirection.com. Dan shared with us the story of the immense emotional, physical, and spiritual pain that he experienced growing up. These wounds made him bitter and desperate. By God’s grace he encountered Christ, but he still retained some of his woundedness and kept barriers between himself to others. At one point, because of his merciless “effectiveness,” he was nicknamed “nuke.” But through growing in intimacy with Christ through the wisdom of the saints, the discipline of prayer, and the mercy of others, even these residual wounds were healed.

Sitting with Dan and one of his friends, I learned that he is now so mild-mannered that his colleagues joke about his class being like a calm PBS show. From “Nuke,” to PBS, Dan would be the first to admit that it’s Christ’s mercy that has made him awake to the presence of God and the dignity of others.

If we admit that we are like the pharisee who stands at a distance from Christ and guards the wounds of his sins, then we can also become like the woman who bathed his feet in her tears. Every vocation requires immense love, and every vocation is a means to grow in perfection of this love. We cannot begin this growth if we aren’t first immersed in Jesus’ mercy. We can’t serve others or adore the Lord with the praise he deserves if we don’t first recognize the ways in which we are numb to God and to people. Who is the hardest to love?

Quite frequently, our man-made visions of our vocations exclude these people, and they also exclude our own weaknesses. These are visions of the perfect version of ourselves, where we’ve escaped those who annoy us and cause us pain, and we’ve anesthetized our own uncomfortable wounds. But this isn’t how the saints did it. When St. Peter, the first pope, recounted the story of the Gospel to St. Mark, he purposely included all of the most embarrassing moments, like when Jesus called him “Satan” and when he denied Jesus. Peter boasted in his weakness (2 Corinthians 11:30). This enabled him to charge headlong toward his enemies with mercy. When true disciples discover the mercy of Jesus, they charge straight into the pain and discomfort of humanity – serving the poor, preaching to those who are hostile, caring for the sick.

So it is worth it to ask whether our vocations have authentic love as a motivation. And where they don’t, we should ask Jesus for the grace to join the sinful woman at his feet, weeping for the times we have been numb to God’s presence and human dignity. There are lots of motivations to pretend to serve God. The pharisee was doing a good job of that. But there is only one motivation to actually love him, and that is mercy.